Deep in the cultural consciousness of a certain kind of American, like a tiny seed waiting to sprout, lives the idea of Walden. Henry David Thoreau might be the grandfather we all wish for, the ancestor that threw it all over for his own beliefs – a true radical who is purported to have replied when Ralph Waldo Emerson asked him why he was in jail for civil disobedience, “Why are you NOT in jail?” This ideal is held fast, as is his challenge to the system in Walden. “by God, I can build my own house.” Never mind that he built it in the Emerson’s back yard and went to their house, or his parent’s house, for supper. Never mind that his mother did his laundry for him while he was there. Never mind that he might have been a fraud. Still, he was a staunch anti-materialist and our first great nature writer and we adore him.

Somewhere as a boy of six or eight I found some scraps of lumber; maybe someone in the neighborhood was renovating a bathroom or building a porch. I dragged those scraps to my own back yard and set about trying to build a house. That was my goal, though I had no idea of how to go about it and no idea that I had only the slightest hint of sufficient materials. My child-thought was that I could lay these boards out in a rectangle and since I could see many houses had boards overlapped on each other as their visible outside (clapboard) I must simply stack boards on top of each other to create the side of the house. It felt urgent and compelling to me even though I gave no thought as to why. Needless to say, that did not go very far, but it did awaken some latent need, because not long after that I recall building a clubhouse with my cousin. He had an older brother, so perhaps he had acquired some knowledge I lacked. This time, we succeeded in making a shelter from two by fours and plywood. Later, as a teenager, some friends and I built another clubhouse in the woods just beyond my backyard. This time we solved the problem of materials by simply excavating our clubhouse into the dirt with shovels and covering the hole with a few boards and the dug soil. We’re invisible, we thought, as we huddled inside with candles.

In The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard, writing about my activities at about the same time I was doing them, illuminates the psychological and philosophical imperatives behind all of this. He suggests that this building/sheltering imperative is a universal one. Perhaps that is true. Perhaps everyone experiences these same desires and manifests them in different ways––card-table houses, tree-houses––and I simply never grew out of it.

Sheila and I had been ardently looking for land to buy in the mountains of North Carolina for most of the previous year. By the beginning of 1981 we’d been living in Tryon for two years, pouring love and energy into The Upstairs Gallery, but also yearning to be a part of the youth movement of back-to-the-landers. We touted voluntary simplicity as a solution to some of the most egregious ills of American capitalist society. Small is Beautiful something of a bible, its title a clarion call, its author, E.F. Schumacher, no doubt also deeply indebted to Thoreau.

John Lennon had been shot and killed at the very end of 1980 and we spent long evenings consoling ourselves at the home of our friends Chuck and Nancy Hearon. We had met them when they had rented us the loft where we were creating The Upstairs above their shop, Tryon Toymakers. They were also kind enough to provide us with a little income by employing us. I was helping Chuck build the toys in the windowless basement wood shop filled with sawdust and power tools: Sears Craftsman radial arm saw, Delta table saw, a bandsaw, a belt sander. Sheila was helping Nancy paint the toys at the back of the street-level shop; their two boys, one in diapers, corralled in a corner by multi-colored plastic fencing, giving the items a test-run.

Something came together during those evenings of shared grief beside a woodstove that inspired Chuck and Nancy to offer to sell Sheila and me a few acres of their farm near Landrum. The twelve acres offered were separated from their other forty acres by a creek and a small lake and it had frontage on a back dirt road to allow us to have our own driveway. Knowing how little money we had, they suggested we pay it off in monthly installments––$125 a month for ten years. No down payment. We decided to accept the offer. It was a god-send and one of those crossroads ––where you choose a direction or it chooses you–– that determines the shape of your life. We concluded the agreement to buy the land by late winter and by early spring we had begun the search for the materials to construct some sort of shelter.

Chuck had a few 4 x 6 treated posts left over from a deck he had built; our friend Craig Williams knew a guy whose divorce had upended his plans to build a garage and who had piles of 1 x 4 tongue and groove pine boards; I found a local sawmill that sold rough-sawn 2 x 4s at half the price of those at the builder’s supply. In 1981, the only permit required in Spartanburg County was for electrical hookup and septic, so we were not bothered with building inspectors telling us not to use rough-sawn pine straight from the tree, or crooked 4 x 6 posts. Assessing the materials we had, and not averse to thinking outside the box, we recognized we could build a 16 x 16-foot square, or with the same materials we could build a twenty-foot diameter octagon and gain twenty percent more floor space, so we settled on the octagon. We didn’t have enough building experience or common sense to realize how much more difficult it would be to build an octagon. I drove my VW flatbed down to Ballard Salvage in Spartanburg and for very little money acquired 2 x 8 tongue and groove heart pine flooring reclaimed from decommissioned railroad cars. They would become our floor.

We chose a building site near the crest of the highest point on the property for our “real” house, and decided to put this building, envisioning we would later make it a chicken coop, up against the trees at the edge of a meadow and just up the slope from the lake – a natural placement that allowed us to drive in along the trees following an old earthen terrace from days when the land was used for growing peaches. There were two maple saplings asking to be front yard trees and a little opening nestled against some short-leaf pines.

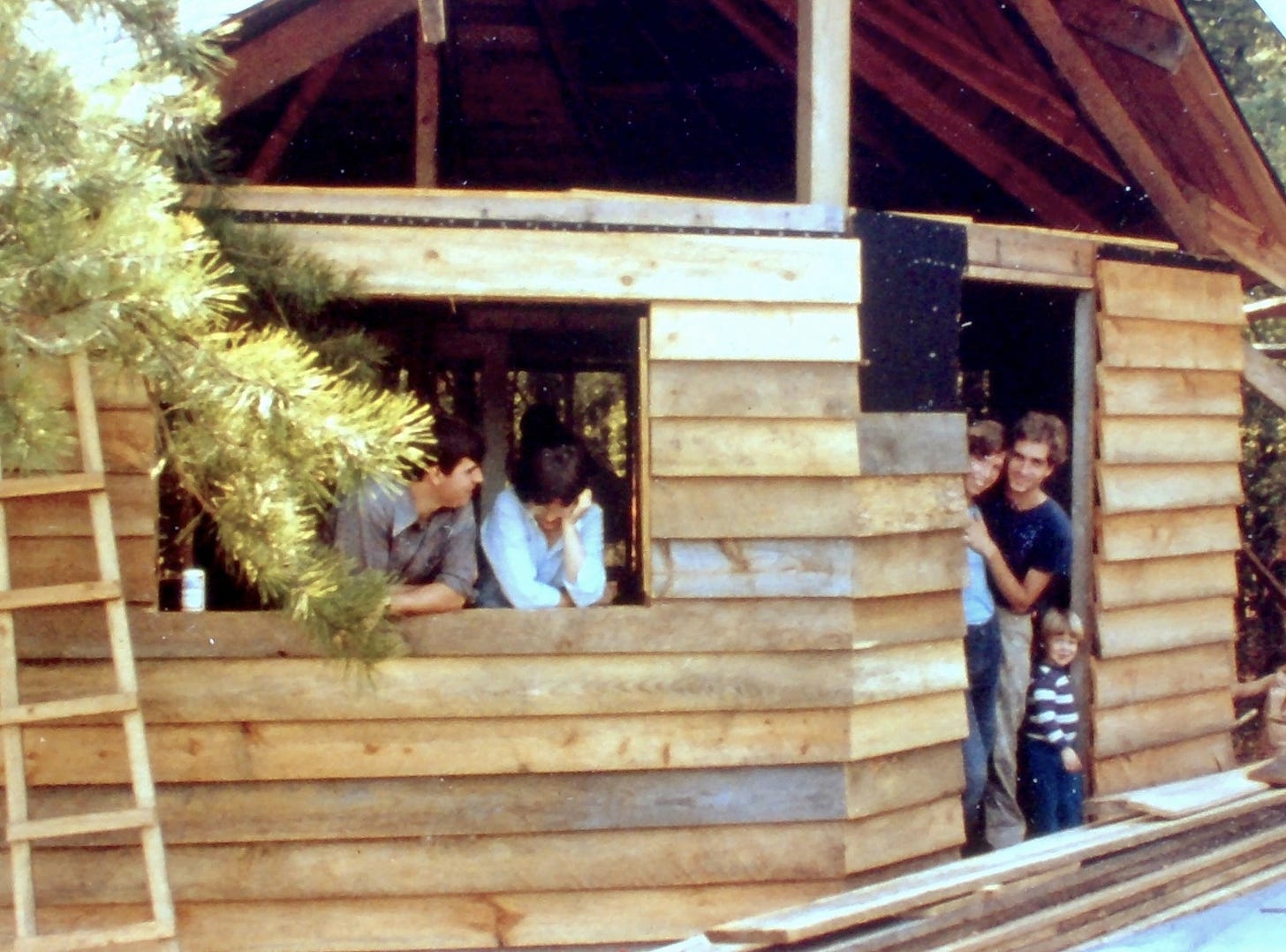

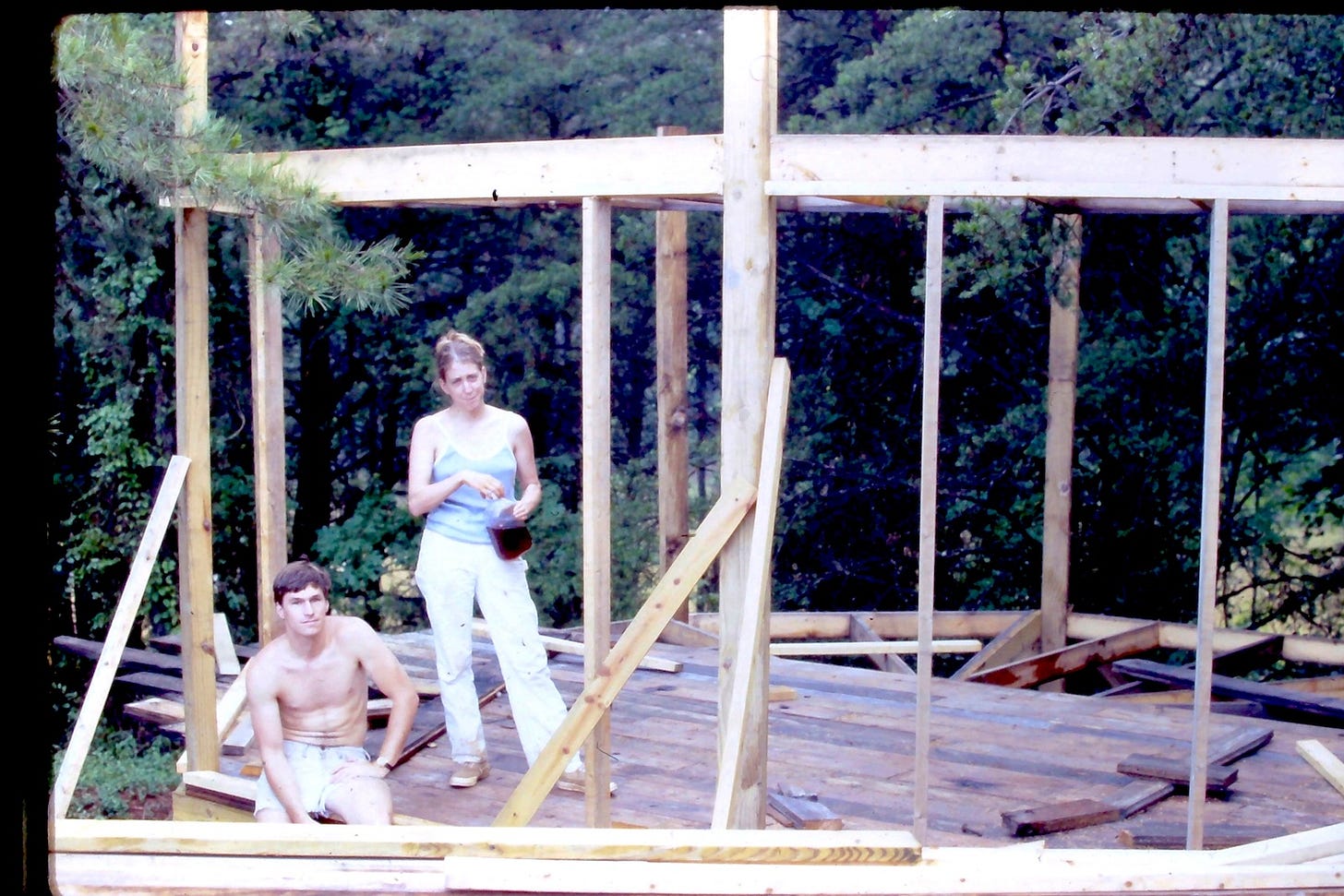

Before long, the chicken coop idea was abandoned and the project was re-christened an art studio. We will live there until we can build the “real” house, we told ourselves. Chuck brought his tractor over with an auger and we measured off where the eight posts needed to be and we were off. Having already been working outside a studio practice for several years, having asserted The Upstairs as part of my art practice, I recognized this, too, as an ambitious art project from the start, a sculpture embodying ideas I had explored earlier and other new ideas. So, as I did with all of my art projects, I documented it as we went along. There are fifty slides of the entire building process, starting in May and ending when we moved in, on my twenty-eighth birthday, the same age as Thoreau when he moved into his cabin. You can see us auguring the holes, setting the posts, nailing up the bands to tie it all together, bringing in one of those rounded ancient refrigerators from the thrift store when there was only a single wall in place so we could move onto the property and stop paying rent. The images go all the way through Phil Nisbet up on the tongue-and-groove roofing boards putting on the shingles. Looking at these slides for the first time in more than thirty years, I found myself overwhelmed by the sweetness of the idealistic young people whose task, taken on willingly and at significant sacrifice, was to alter the culture.

There I am trying to prove it was not necessary to indenture oneself to a bank for 30 years in order to have a viable home. There is Sheila who, astonishingly, was able to wake up at our construction site (because we had expected the job to be done so quickly, we had moved out of our house in Tryon and given it to The Upstairs Players for the summer) then dress and head off to work at Isothermal Community College.

Some days she stopped at her brother Tad’s house for a shower. Tad had recently graduated from Bowman Gray medical school, his tuition partially paid for with a Federal grant that required him to work in an underserved community, so he and his wife Anne had chosen to move to Landrum for two years––the underserved community where Sheila and I lived. There are Tad and Anne above, leaning through the unfinished window.

There is Chuck, ten years my senior and far more experienced, leading the construction in the generous understated way that allowed me to tell myself I was building my own house. There is Craig Williams who helped us find materials and a gorgeous six-foot long enameled cast iron sink being given away because it was old-fashioned. There are Claude and Elaine Graves, the local potters who threw big parties at their studio that cemented this community together. There is a group of young people who came over on July 4th for a roof-raising: Clay Spencer and his friend Ronnie Patterson, who were actually skilled carpenters. “Hey,” one of them shouted from the loft as a rafter was being placed, “is there such a thing as a chisel on this job site?”

Long pause…. “No, sorry. Will a knife work? Or a screwdriver?”

Over the course of six months, we had visitors from all over, all of them pitching in in one way or another. Friends from earlier moments in our life: my junior high friend Duncan came over from Charlotte; Sheila’s younger brother John, in town to lead The Upstairs Players. Sheila’s brother Larry and our college friend Nancy Weaver came over from Winston-Salem, and there is Fletcher Carter, now dead of Parkinsons and dementia, in the loft doing something –wiring? A friend from college who was one of the leaders of the Outing Club, Fletch lived in Roanoke Rapids, but must have been in the western part of the state for a backpacking trip. All of these people either believed in or were participating in the same cultural revolution. We had rejected the world of corporate capitalism and were building our own houses, starting organic farms, creating a cooperative community in nearby Green Creek, making a living throwing pots or building wooden toys, or making art.

How did it all end? None went into the corporate environment. Some ended up as teachers or therapists, others remained artists and craftsmen their whole lives, but the world was not changed much, or at least not visibly so. Some seeds were planted, some medicinal herbs were nurtured, children were influenced. The “real” house was never built. As these words were first being written in 2020, there were demonstrations in the streets all over the country protesting the systemic racism that has allowed black folks to be treated cruelly all along, and those protests offered a promise that other miscarriages of justice might also be addressed. But they are the same miscarriages we railed against forty years ago, and now a newer and much more cruel threat looms.

But, from the vantage point of a forty-year remove, we might say that although cultural transformation is excruciatingly slow, that it comes with thousands of smashed fingers and cut thumbs, that it drives people stark-raving mad with anger and frustration, that it seems never to be on the horizon; that once in a lifetime, as the great Seamus Heaney wrote, the longed-for tidal wave of justice might rise up and hope and history will rhyme. Or as Thoreau himself wrote, “It is something to be able to paint a particular picture or to carve a statue, and so to make a few objects beautiful; but it is far more glorious to carve and paint the very atmosphere through which we look, which morally we can do. To affect the quality of the day, that is the highest of the arts. Every man is tasked to make his life, even in its details, worthy of the contemplation of his most elevated and critical hour.”

An impressive recollection, not only of the process you went through over such an extended period of time — its inspiration as well as the patient implementation — but also the connection and adherence to your overall artistic approach. Not to mention the power of recall you seem to have ... Enjoyed the reading, as usual.

So inspiring.