Yesterday I re-stacked a post from Lasley Gober’s Substack, a meditation on letters from her dad, Dave Fick, during World War II. Doing that called to mind this essay, which long ago hit the cutting room floor. Perhaps it should stay there, but apparently it has a mind of its own. It was originally a chapter called The Gift.

There is the canvas and there is you. There is also something else, a third thing…you have as a measure – and once you have experienced it, nothing less will satisfy you- that some other being or force is commanding you: ONLY THIS shall you, can you, accept in this moment. -- Philip Guston

I kicked my feet against the white clapboard by the front door to dislodge the snow packed in the cleats of my two-pound Vasque hiking boots, pulled off my toboggan and slapped it against my leg, opened the door without knocking, and stepped into a worn but comfy living room. Across the way, my high school friend Duncan sat by the fireplace poking at some embers under a chunk of damp wood, blowing on them to try to muster some flames. The snow had begun in the middle of the night and by morning half the teenagers in town had dialed the official number that let us know school would be cancelled on this generic winter day in 1971.

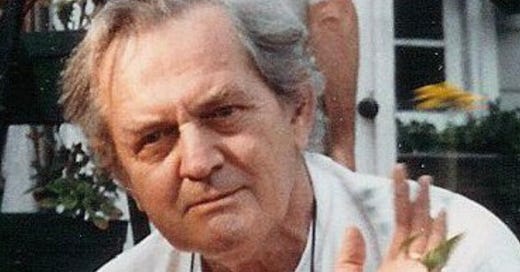

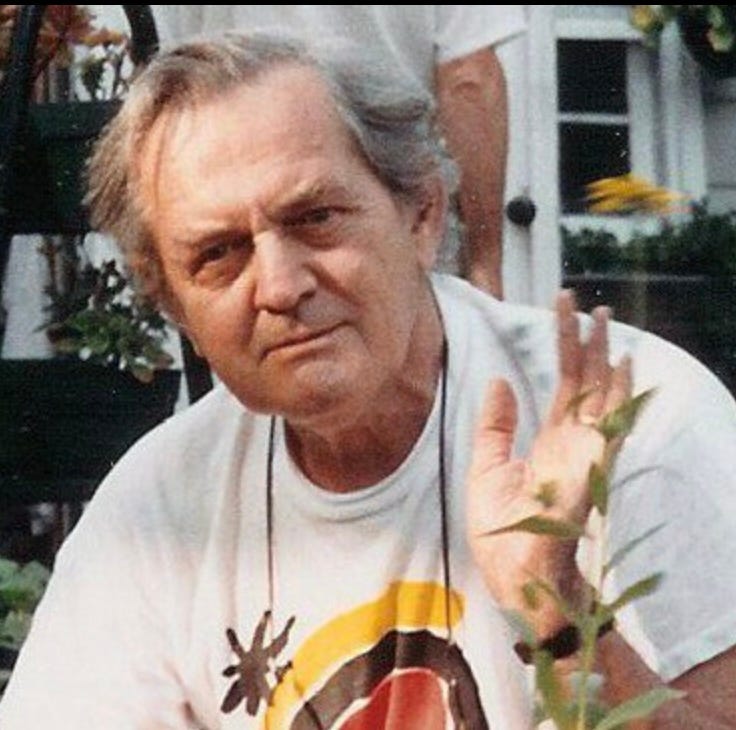

Duncan hadn’t called to invite me and I hadn’t called to say I might come over, I just pulled on my boots and coat and toboggan and slogged off into the snowstorm. It went without saying on occasions like this that kids would gather at Duncan’s house, though none of us ever thought to wonder why. Looking back, I see that his parents were part of the reason. Open-minded, welcoming, and a little cooler than most other parents, Duncan’s mom, an English teacher, was knocking around in the kitchen at the back of the house and his dad was in a small room just inside the front door. I don’t remember what they called that room, maybe “the den,” but now I recognize it as an artist’s studio. Dave worked at Alderman studios, an advertising firm, but he spent many of his free hours in this small room that smelled of turpentine and linseed oil and that held dozens of small canvasses in various states of completion: portraits, blue horses with red hooves, flowers that looked like they belonged on an album cover for Lysergic and the Diethylamides. Nothing like this would have ever appeared in my own home.

An hour later, Duncan and I still by the fire, Dave poked his head out of the studio door to look at us. Half-moon glasses rode low on his prominent nose, his gray hair longish and combed back. A moment later he brought out paper, India ink and quill pens for each of us and suggested we draw something. Maybe we were being annoying; maybe we were just being slothful enough to inspire Dave to direct us. Maybe it was just a random moment. Did he give me the magazine photo of a small boat in a rough sea or had I, lacking imagination, picked it up? No matter. What happened was a revelation. The drawing that I produced was remarkable not just to me but to Dave. Had I done that? How? Maybe the day had slowed us down enough that I was able to focus on what I was seeing or maybe having been given only one sheet of paper and uncorrectable ink had forced me to slow down and look carefully. But not everyone is able to coordinate eye with hand to follow and reproduce the contours of something. No one had ever spoken to me of this before. I had never attempted it before. It was the first moment I experienced the phenomenon that most artists discover at some point and then chase for the remainder of their lives, something beyond conscious control, something inexplicably working through me, directing my hand, controlling my mind––something magic!

Within weeks I would take up a pen again and translate a deep admiration for the comic strip Pogo into my own road map. Having watched in wonder as Walt Kelly had taken on the absurdities of the Nixon administration with his swamp-living stand-ins and having come to political consciousness along with so many baby boomers through the televised war in Vietnam; feeling a deep sense of futility and impotence as a teenager in a nowhere town, I recognized this as a potent way to speak out. I began drawing satirical cartoons for The Pointer, my high school newspaper. The revelation of having done this drawing, or of the drawing somehow happening through me, hovered seductively in the dark corners of my mind, biding its time, crafting a logical way for “me” to be drawn back to “it.” I became captivated, compelled forward, not having any roadmap for where I was going, not knowing whether such a place even existed.

The next year I created a comic strip for my college newspaper at Wake Forest and began to pick at the knots of the respectable-southern-male-upbringing idea of you-can-only-be-a-doctor-or-a-lawyer. My decision to create a comic strip for The Old Gold and Black might well have been simply dismissed. Who was I? A freshman from nowhere. What had I done before? Three cartoons for my high school newspaper. I have no recollection of how this happened. What did I submit to the upperclassmen that served as the editors - an idea, a few samples? The editors were Tom Phillips and Malcolm Jones, who went on to a stellar career at Newsweek. My memory is only enthusiasm, mainly on the part of Malcolm, whose delighted and slightly devilish smile I still recall, his eyes crinkled behind wire-rimmed glasses. Did he like that I was willing to throw bombs? That I was willing to flaunt propriety? Who knows, but he green-lighted a full-page comic strip about the adventures of a booger for the literary magazine, where he also served as editor. A different reaction might have communicated that I was not smart enough or a good enough artist (both true,) or otherwise not worthy of continuing down this basically unmarked track I had imagined for myself. But Malcolm not only encouraged me, he arranged to have me paid each week for my comic strips. So right away I found a way to be an artist and to be paid for it, but more importantly I laid groundwork for a conception of an art that depended on content, an art that was engaged with the society it sprang from and, not inconsequentially, I found a platform from which to vent the steam of adolescent frustration and righteous anger. Mostly that steam was directed at the administration of the college, which I dubbed Wake Farce, but given my platform, that was the appropriate target: a target and a society that I could actually conceive of influencing by my satire. Railing at the Nixon administration from The Old Gold and Black would have been useless.

So I continued penning a modest cartoon strip, but also crafted a January term course of independent study of cartoons as art. I contacted Gary Trudeau, Walt Kelly, and a few others to ask if they would permit me to visit. I spent hours in the library studying the history of the cartoon, discovering The Yellow Kid, Little Nemo, and perhaps most importantly, George Herriman, the creator of Krazy Kat. While Walt Kelly had captivated me with incisive political commentary, memorable characters and gentle humor, George Herriman pointed the way to a darker, more cerebral but also more cathartic world. A world where objects portrayed in two dimensions and in black and white could transform before your eyes, becoming abstract sculptural objects of beauty and mystery, a world where obsessive love was mixed up with offhand violence, where gentle characters were not always the winners; a more complex world – one that resembled an artwork. This discovery tilled the earth in front of me so that when I discovered art beyond pen and ink, I was able to recognize it. Inspired by that, I took a class in Modern Art, beginning of course, with Eduard Manet and his ideas of what painting should be; then to the shocking work of Vincent Van Gogh, the radical ideas of Cezanne and Picasso. By the time I encountered the subversions of the Surrealists and the transformational propositions of Dada, I was a goner. By the end of the semester, I had decided to change my major to art and become an artist. Because Wake Forest did not have a studio art major, I had to leave Wake Forest and find another place where I could study.

Many times I told the story of the importance to my life of this young professor who had taught the course with so much passion and insight. Years later, when I found that she was having an exhibition of her own work at a local college, I went to the opening to find her and thank her for having opened my eyes to the transformational possibilities of art. I don’t know what I expected: maybe she would embrace me and thank me for acknowledging her role in my life, maybe she would invite me for tea to hear about my career, maybe she would tell me about her own life’s arc. Perhaps I should have chosen a different moment for my message. This moment, of course, should have been about her, not me, but I naively thought my account WAS about her. I guess she didn’t see it that way. I said hello, told her that I had been a student of hers at Wake Forest and before I could say another word she turned and stepped toward someone else.

Oh well. She changed my life, too, but if not for Dave Fick, if not for that random day in front of the fire with a piece of paper and a bottle of India ink, would I have discovered Krazy Kat and the threshold into the alternate world I have now inhabited for fifty years? Probably not.

Thank you, Dave … and Malcolm … and you, too, Penny.

What a thrill, reading this. Thanks so much for sharing with all the Ficks, including Mom (age 98), and ensuing generations emerging from the pair who gave us life and light, and you, warmth and inspiration.

Although you and I were always hovering around each other during these early days of you becoming an artist, I never appreciated the details of how you came to be such. So thanks for this recounting and also the appreciation of my Dad's role.

On a side note, I do remember you considering University of New Hampshire as we were making our way to Montreal that winter of 1975. And shopping the art supply shop in Concord during our layover for the bus.