Early November 1975, I’ve just turned twenty-two and I’m nearly naked beside a body of deep, clear water near Chapel Hill, NC. My arms are wrapped around my chest against the chill, my yellow boxers blow against my bony hips and skinny ass. All around me are large gray boulders set in a sloping grade covered with the crushed gravel of a rock quarry ––abandoned because it has filled with water. A man and a woman stand nearby with cameras, both dressed more sensibly.

The woman is Ellen from my sculpture class. The guy is my friend Richard, who will one day sell his photographs for high prices to soft-core magazines and then fashion glossies and then art collectors. But on this day no one has heard of him. He’s an art student, like me and Ellen. We have rejected traditional ideas about art and have embraced the radical ideas we find in The Fox, a short-lived magazine of conceptual art created by Sarah Charlesworth and Joseph Kosuth, or Avalanche, Willoughby Sharp’s provocative art magazine. It’s late 1975 and the world is on fire. Pol Pot has seized Cambodia, helicopters have evacuated personnel from the roof of the U.S. Embassy in Saigon, Nixon’s accomplices have been convicted and two different women have tried to shoot President Ford.

We are convinced that pleasing forms, be they sculpture or painting, are the playthings of the rich, something made only to be bought and sold, something to invest in, to bet on, like stock cars or race horses. That’s not what I signed up for. Robert Rauschenberg had pronounced that he wanted to operate in the gap between art and life. For this pronouncement he got tons of critical praise, (and sold lots of artwork) but in 1975, he had not actually done it. My quest, at twenty-two, is to actually do it, turn my life into art, but I don’t yet know how to go about it. I’d built sculptures from natural materials in the depths of the National Forest, locating them with Geodetic Survey markers; I’d shaved off the right side of my five-inch beard and walked around in public for a weekend as a way of mocking convention and conformity, but also as a way of asserting my self––my life–– as an artwork.

“You’ve come too far, too fast,” one of the sculpture professors says to me. “Suddenly, you’re out there somewhere with Vito Acconci and Chis Burden. Maybe you don’t know what you are doing.”

Yes, Acconci’s crazy performance pieces––masturbation under a false floor in Sonnabend gallery––and Burden’s provocations––having himself nailed crucifixion style to a VW bug––have gripped my imagination. I am in accord with their revulsion and their tactics. “Why do you think the job of the artist is to deal with form and space in a pleasing way?” I ask my professor.

He stares at me.

“Why shouldn’t art be about real life?” I say. “Why shouldn’t we live our lives as if they were works of art?”

So I set myself on that path, trusting there might be a few blazes along the trail cut by other artists seeking a new way forward, but knowing that eventually I would have to forge my own way; not knowing the destination; not knowing even the crossroads until I come upon them and am forced to choose one path or the other.

On the shore of the quarry are forty Styrofoam microscope boxes I’d scavenged from behind a science building on the UNC campus. My idea is to string these boxes together with something imperceptible so they are connected to each other but not visibly so and then to exploit the inherent property of Styrofoam, which is ninety-five percent air, and float them in a body of water, allowing the wind to blow them into different configurations. I believe this is an artwork about the immanence of the natural world.

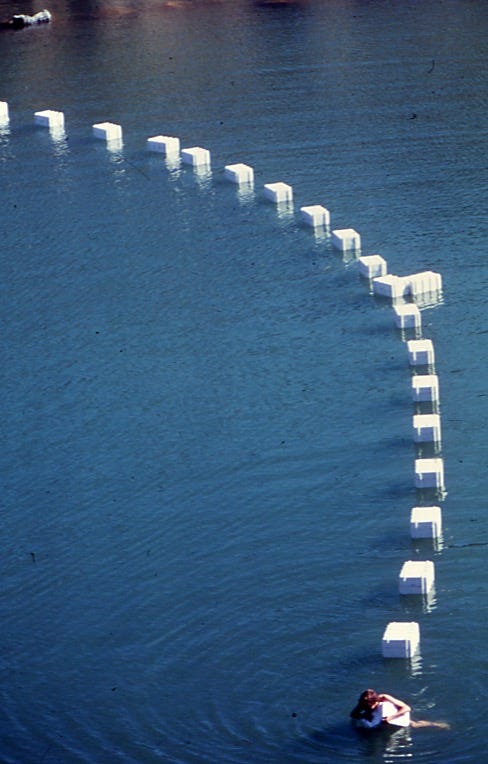

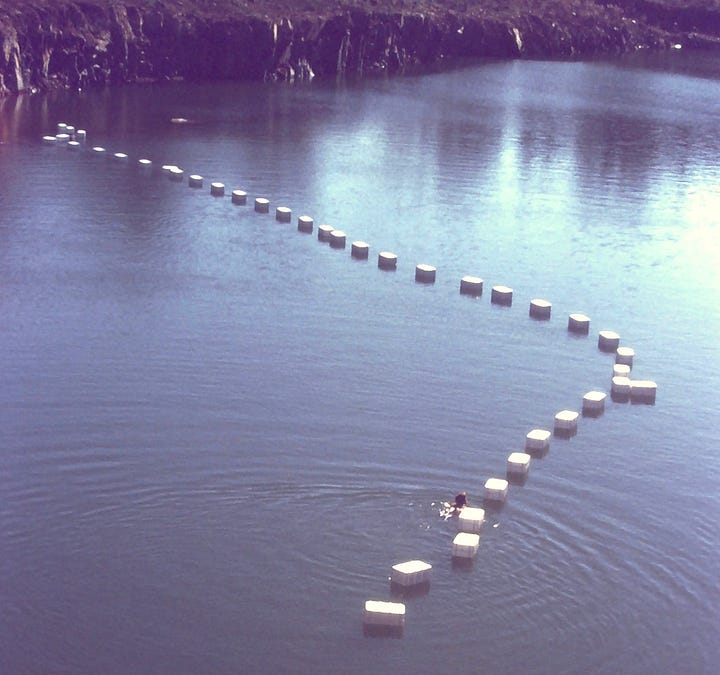

Shivering a little, I stick my toe in the clear water and feel the gooseflesh prickle my thigh. I brace myself and wade into the water, the stones and the cold instantly making my feet ache. Holding the first white box to my chest, I frog kick across the icy water as Ellen feeds the other boxes into the water one by one behind me. Richard is on the cliffs with his camera. I think the random action of the breeze will create patterns that will somehow be more authentic, more evocative, than the patterns I might make consciously. Richard begins documenting the event with color slides. The group of forty boxes trails behind me across the entire quarry, a slight breeze bending the line into an exquisite arc. I swim back to shore and pick up my own camera and hustle to take a series of black and white photos of the resulting combinations and compositions.

In 1975, Forty Boxes was a transient and time-based piece, but only three viewers experienced it in person; the artwork presented as documentation was exhibited only once as black and white photos, seen by a dozen classmates. I failed to ask myself at the time whether my radical idea had influenced anyone, or had even reached an audience. Maybe back then I would have said I was simply in training, or maybe I hoped for a more illustrious future for it. With luck it might now be locked away in the warehouse of some art collector. In 1975 there was no other paradigm.

But because the ownership of this piece did not transfer to a collector, it now exists as a different kind of time-based artwork with a different distribution system; one you can follow by reading these words or by looking at the photographs taken by Richard and by me. That day at the quarry, we saw order, entropy, and the surprising beauty of a few brief moments as order gave way to disorder, but the truth is the natural world did not deliver those most beautiful moments. Richard and I did. Ultimately the forty boxes ended as a jumble of objects deeply uninteresting and visually unappealing, even repugnant, nothing more than decay-resistant flotsam floating alongside cans and bottles. Now what I see when I look back at it are a few choice moments selected by two human beings.

Now, I understand beauty is not a lesser goal, a debased goal. It is a tool of the highest goal. Now for me, the aesthetic pleasure far surpasses the intellectual pleasure I originally intended. You, the observer, decide where the beauty lies. Is it in the juxtaposition of geometry against the natural world, the unnaturally white boxes and the crystal subterranean water? Is it in the color relationships of the azure water to the burnt sienna and Payne’s gray of the quarry rock? In the sparkle of sunshine reflected into the lens of a camera? Or, absent the color of Richard’s photos, maybe the appeal is the compositions in black and white I chose as I bent low with my camera and opened the shutter for an extended time, the choices I made about how deep to make the blacks as I hovered over the developer tray in the soft red light of the campus darkroom.

These are human interventions. Nature blew the boxes around but didn’t care about the way they looked. Left alone, nature would eventually break it all down and put it to some other use. Robert Smithson, whose iconic basalt Spiral Jetty coils into the Great Salt Lake, claimed this entropy as part of his oeuvre, but Smithson, too, was young. And wrong. It is not the entropy he embraced that redeems his work, it is the order he imposed on that entropy. Yes, the Salt Lake rises and obscures, and yes, such entropy is part of the artwork, but the absurdity of the coil and the stark beauty of the spiral jetty that sinks and then re-emerges is what calls us to it. The bravura physicality of the riprap endures fifty years later and will exhilarate us fifty years from now even if the lake has disappeared. The why of that––mystery within mystery.

But what endures here with Forty Boxes? Without these words and the accompanying photos, the artwork would exist for no one. It would be locked away in a little metal box of Kodachrome slides and then at some point it would be discarded, having never been shared. Maybe the art experience (does it matter whether we label it art?) depends upon you scrolling through the photographs posted online, choosing what to focus on, what to accept from me or from Richard, what to open your eyes to, what to open yourself to. Or perhaps the only residue of this artwork will be the brief exchange between the old man sitting here and the idealistic young stranger who determined the course of that man’s life.

I love your stories, Craig. When I was in grad school at GSU I moved out of my little house several times and gave it to visiting artists for the weekend or week. One was Willoughby Sharp. In exchange, he let me photo copy his oversized address book. I still have the big stack of pages.

Thank you for these generous and richly contextualized posts Craig, they are such a pleasure to see and read. You bring the art back to a life and then set it free to float in these currents wherever it may go. Beautiful and still radical.