A few months after Julia’s birth, Sheila and I decided to embrace the uncertainty of it by creating a two-page tabloid-style birth announcement patterned after The Weekly World News, a hyperbolized headline-screaming laugh-riot sitting upfront on every corner newsstand in New York at the time. We used actual headlines from The Weekly World News: WOMAN HAS BABY IN HER SLEEP, was our lead story accompanying a picture of Julia asleep. OUR BABY WEIGHS 250 POUNDS! We produced a hundred of these and gathered up addresses of every friend we could find and started into mail production. Sheila’s final touch as they were being stamped, was to put a little red rubber-stamped image of a stork above the fold near each address.

About three months later one of them was returned to us. It had been addressed to my college friend Taylor. We met in a Wake Forest January-term course called American Communes and Utopias assembled in a “commune” on the Isle of Palms in South Carolina. I had later adventured with him in Morocco. He had graduated from Princeton Theological Seminary and in 1979, had performed his very first marriage: mine and Sheila’s. Last we had heard, Taylor had departed Hong Kong and was enrolled at Golden Gate Theological Seminary near San Francisco, so we used that address. We were wrong. He and his wife Susan were no longer there, but some kind soul attempted to forward the announcement to them and had written the address on the front and put it back in the mail. At that point, a harried postal worker grabbed it, evidently glimpsed the stork image, which to his trained, yet overworked eye, looked for all the world like the little “return to sender” rubber stamp some of us remember –a hand pointing to the return address– and sent it back to us. We were living at 337 East Ninth Street in Manhattan. The forwarding address was 190 East Seventh Street, four blocks from our storefront apartment. Poetic coincidence. I was amazed and delighted. The next afternoon, I went out our front door and headed east through Tompkins Square Park toward the address on Seventh. No one home. I wanted Taylor to get the same kick out of this as we had gotten, so I decided to surprise him. I went back home, rustled around and found a picture of Julia. On the back I wrote, “The parents of this child would like to invite you to dinner Friday evening at seven. Please come to the east storefront of 337 East Ninth Street,” and I slipped it into their mailbox. On Friday, we prepared a nice dinner, set up a table by the fireplace at the front of our narrow apartment, and waited for Taylor and Susan to show up. I could hardly wait to see his reaction to find me living only four blocks from him after having not seen each other for six years.

They didn’t show.

“I told you they wouldn’t show,” said Sheila.

I dragged out the three-inch thick phone book and not finding Taylor, found a number listed under Susan’s name.

Susan answered.

“Could I speak with Taylor?”

“Could I ask who’s calling?”

I wanted to hear his surprise, “I’d rather not say.”

Susan was no pushover. From North Carolina like Sheila and me––her father had worked in J.B. Rhine’s parapsychology lab at Duke–– she had come north to do social work in Harlem. “Well, I can’t let you speak to him without knowing who it is.”

Finally, when she put him on, I told him where I was and then scolded him for what I thought was a lack of adventurousness. “Taylor, you would allow yourself to be led into the labyrinth of the Marrakech medina by a twelve-year-old but you wouldn’t accept a dinner invitation from a stranger four blocks away from you in New York? I’m disappointed in you.”

“Craig, if you knew the kind of people I’m associating with right now, you would understand my hesitation.”

It turns out he had gotten the note and had walked over to check out what he might get himself into. Seeing our storefront with its grimy cracked window, the accordion grate pulled across it and fastened with a two-pound stainless steel lock, he decided he’d better pass.

He had completed a Masters of Divinity at Princeton, had graduated from Golden Gate with a Doctorate of Divinity and rather than go into some wealthy suburban mega-church, he had chosen to serve as pastor for the tiny mission church on Seventh nicknamed Graffiti, a church whose parishioners were drug addicts, alcoholics, and the sizable homeless population of Loisaida. Later they did come over. We reconnected, discovered we had children the same age and became fast friends once again, Susan arriving each morning at our storefront with coffee and her two boys. I would bundle Julia into her stroller as Sheila headed off to the NYU Linguistics department and Susan and I would spend the morning dodging the kids through the tents and needles of Tompkins Square or in the playground of Washington Square. My new job at NYU’s 80 Washington Square East gallery started at eleven o’clock so I dropped Julia at the Linguistics department where Sheila installed her with a baby monitor in the sound isolation booth usually used for the research they were doing as early pioneers in speech recognition and speech synthesis - (yes, Siri and Alexa.)

Soon, Taylor invited me to help him at Graffiti’s Wednesday evening soup kitchen.

I arrived at the little storefront early that first Wednesday. A single step was the demarcation between sidewalk and mission. The room was small and cramped with a well-worn linoleum floor. The walls needed a coat of paint and unapologetically showed the marks of chairs rubbing against or banging into them. A cheap card table was set up against the right-hand wall and held a large coffee urn, a teetering stack of Styrofoam cups, packets of sugar and a plastic tub of generic “creamer.” In addition to Taylor, two or three others were already there. Linda, a short, slightly rotund woman of fifty or fifty-five, cheerful and smiling, bustled around the small room setting up chairs. It was early autumn, crisp but not yet cold. Linda looked as though she might be storing most of her wardrobe on her person. Something in her gaze unsettled me further. Perhaps she looked directly into my eyes, something not done by New Yorkers at the time, or maybe the willingness to look me in the eyes allowed me to glimpse something slightly uncanny or wild about her gaze. I couldn’t place the intuition of warning, so I trusted Taylor and let it go.

Then a man of indeterminate middle age turned to me from his task of making coffee and put out his hand. His clothes had certainly not been washed in weeks. The bottoms of his too-long jeans were worn ragged in back where they dragged the ground behind his shoes. The hand he offered was etched with fine black lines in every crease, his red hair had a patina of oil. “Hey! I’m Frank.” Taylor was close by at the moment and said, “Frank, this is Craig, a good friend of mine from college,” and abruptly turned to speak to someone else. At this moment my consciousness shifted. It was patently obvious this man whose hand I shook was one of the people I had looked past a hundred times. Homeless. I am embarrassed to admit that even having traveled through the desert of Morocco, I had never had an encounter with someone whose life was quite so different from my own, someone I would cross the street to avoid in any other situation, someone I was afraid of.

I’m often at a loss for how to make pleasant conversation even with people I can relate to, but here was someone who lived on the street, who begged for money, who had no job, and whose circumstances, in my mind, could not have been of his own choice. How to begin? “What do you do?” No, I couldn’t say that because he might do nothing but beg. “Where do you live” no, that would feel intrusive of someone who probably has no place to live. “How do you know Taylor?” No. “How long have you been in New York?” No. What is the opening remark? The recognition of his otherness and simultaneously of his obvious ease and normality confounded me. I couldn’t nod and smile as I might have done in Marrakech, this guy was an English speaker and not much older than myself! Coherent and even helpful –more at ease here than I was! Taylor had a familiarity and a relationship with him, why was I intimidated? Why did I expect he was not fully my equal? Why did I feel as though he might be embarrassed by my questions, that I might be embarrassed for him to have to answer them? But he was not embarrassed by his circumstance. The mental problem was mine. Prejudice. False Assumption. Hypocrisy.

Frank was indeed homeless. So was Linda, though Linda at least had managed to claim a squat in an abandoned building a couple of blocks away. She was a former nun, which possibly explained the beatific look in her eyes I took for a touch of mental illness. Frank, it turned out, was an attorney––until the death of his brother.

There was soup. There was free-flowing coffee. As more people arrived, mostly appearing to be even worse off than Linda and Frank, Taylor said a prayer over the food and invited them to gather chairs around to sing a few songs. Each person was treated with the same kindness and respect all of us expect in normal day-to-day interactions. As Taylor went from one to the other, I had a vision of myself turning my face from them as I walked down this very street. I saw them being ignored, saw them watching someone like me cross the street in order to avoid them. I saw that even the gesture of handing them a quarter or a dollar somehow demeaned them. This humiliation was the life they led most of the time but it was not their experience here. The revelation of this place of kindness and civility and normality turned my life upside down.

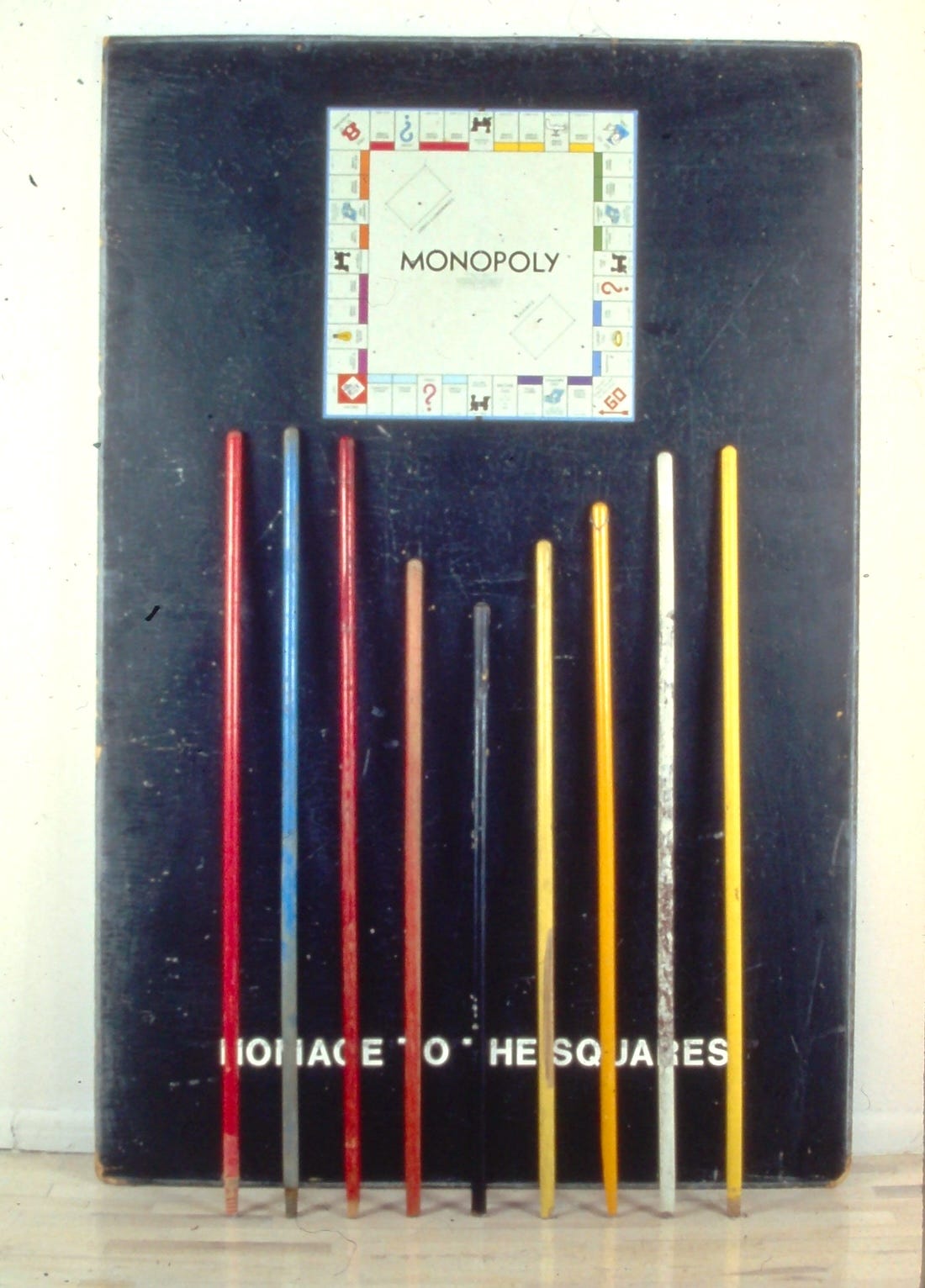

I began volunteering on a regular basis on Wednesday evenings. Gradually, I felt more at ease, began to have conversations, learning the smallest of misfortunes has the ability to throw a person into dire circumstance and onto the street: the death of a brother, the failure of a marriage, a trip to the hospital. I met several people who identified as artists and one, JR, who seemed to know all the others. JR lived in Central Park and told me he regularly buried the artworks he made as a way to store them. This struck me as somewhat bizarre, but I just nodded, as if this were a perfectly logical storage solution. After all, I faced the same problem of storage for the sizable installation pieces I was doing. I solved it by making work in components that could be taken apart and stashed. That work disappeared just as thoroughly as if it were buried. Most of it is now lost, existing only in visual images.

I don’t recall who hatched the idea of organizing an art exhibit of work by these homeless artists at Graffiti, probably Taylor, but I volunteered to coordinate and hang it, relying on JR for most of the contacts. We put it up at the storefront church. A few weeks later, attending an artists’ open-call meeting in Soho, I volunteered to mount a similar exhibition as part of Martha Rosler’s exhibition “If You Lived Here…” which was mounted at DIA Art Foundation’s Wooster Street space. A multi-part investigation into the politics of housing in New York, it included the work of architects, planners, and many well-known artists in addition to the homeless artists I had met through Graffiti. Forward-looking and socially engaged and now seen as a seminal exhibition, it was virtually ignored by the critics and art press of the New York art world at the time. Its admirable strategy was to hijack an art venue to try to catalyze new perspectives about a social problem. Its failure, which sadly presaged the political failure of similar work to come in later years, lay in its hermeticism. Like my own work at the time, it spoke to the wrong people.

This is one of my favorite entries in your book partly because of my experience with homeless persons. Your first meeting with Frank so well described! Thank you!

Hi Craig! I don’t know if you remember me but I had a residency at VCCA many *many* years ago. This is such a wonderful post! So heart-opening. (I have a substack too, on art/creativity informed spirituality and social justice.)