This multi-platform, intermedia project I have embarked upon is far more work than I imagined or intended. Some days it feels like an archeological dig, other days just overwhelming, like excavating and emptying a house you’ve lived in for fifty years. What to do with all the shit?

Take the year 1989. I’m brought to it by the memoir entry about Black Mountain College, but find, when I open the box, not only is there the birth of our second child, the adventure at Black Mountain College, the uprooting from the East Village and move to Virginia, the year is jammed full of an enormous body of work, twenty or more pieces. Some of this work was never seen, and lots of it was assembled for the duration of the exhibition at The Upstairs and then taken apart, ceasing to exist, back to its component parts, but some of it was written about beautifully and lucidly in reviews in The Arts Journal by Alan Sondheim and in Atlanta ArtPapers by someone writing under the name of Isidore Ducasse, the Surrealist poet who died in 1870 at age 24. Then there is the catalog essay that accompanied the show, written by Bill Arning, the storied director of White Columns in New York.

Unlike the criticism, that essay was less steeped in theory and artspeak and for someone unfamiliar with the historical context or put off by seemingly esoteric gestures, it offers something of a road map. Feel free to skip it, but for those who are interested, I offer it here, with thanks to Bill Arning.

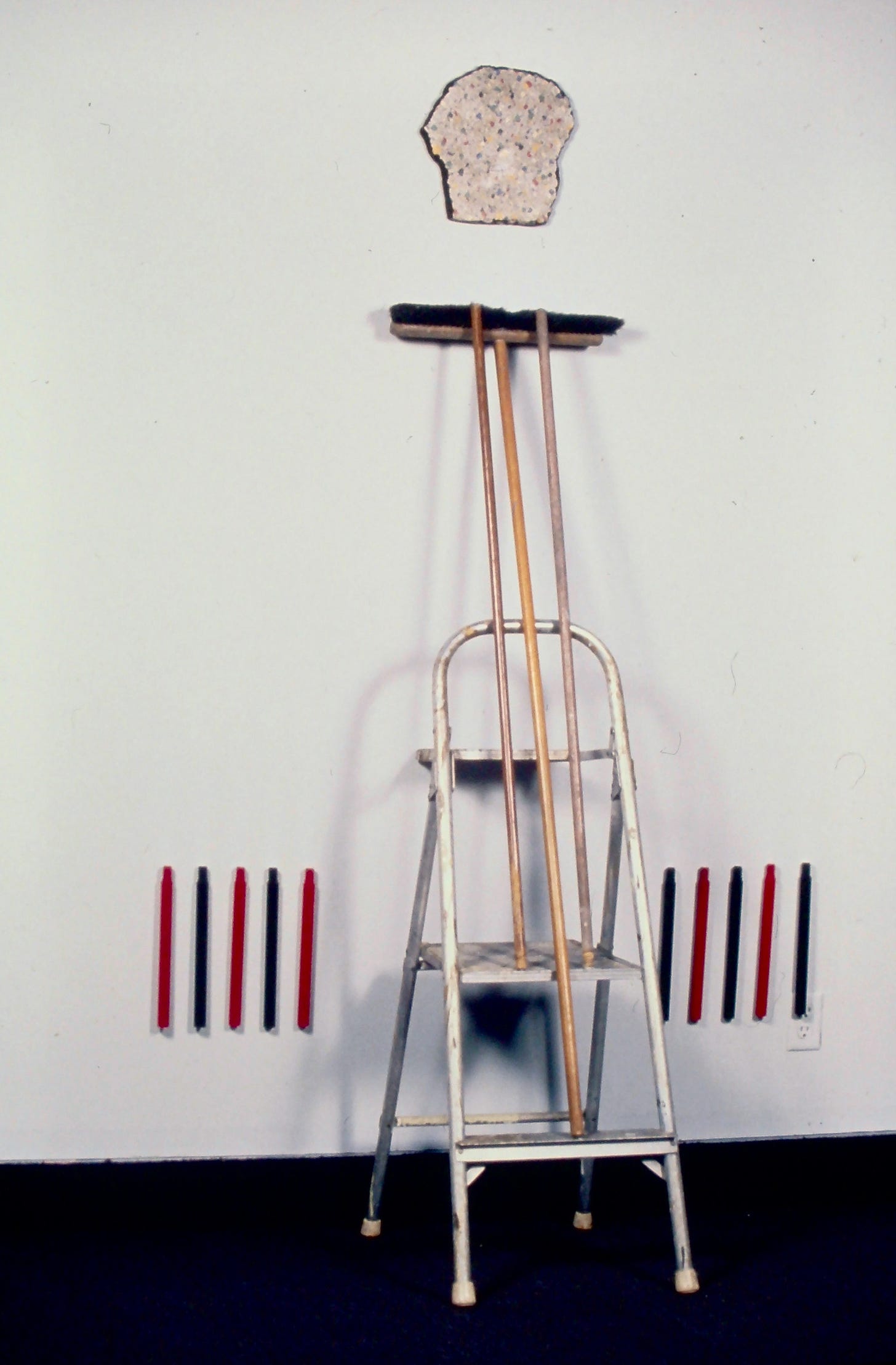

A small patch of floor covering, irregular in shape, its design faux-elegant and its colors faded from time and use, would seem to be the least likely of materials to allow for rich layers of interpretation. Craig Pleasants' work is based on just such refuse, and through a remarkable series of barely perceptible interventions he creates a unique and quite beautiful body of work. Pleasants selects materials that are lowly but, upon reflection, full of associations. The floor coverings have the aura of domesticity. They, along with the broom and mop handles, show evidence of endless hours of housework. Lives have been lived on these surfaces, but time has moved on and they have been discarded.

It is interesting, while considering Pleasants' work, to note that he has reversed Carl Andre's radical gesture of locating the art work under the viewers' feet. For one exhibition he found floor tile identical to that of the gallery floor and mounted it on a wall; the viewer was looking at the same pattern and substance on which he was standing.

Pleasants rarely alters the shapes of the found linoleum. The shapes have more resonance for the artist if they are produced by someone else who had no idea of art, or of making anything beautiful. He also questions traditional modes of art making and artistry by not allowing himself to aestheticize the objects, except by finding coincidental associations of the shapes and patterns and through incorporating other found elements. Pleasants has decided to create art without fabricating anything, without generating another object to further clutter the world, but rather to subtly transform valueless objects, saving them from the trash-heap. This results in an almost zen-like beauty and quietude.

An association to Schwitters' Merz pieces, made with similar materials, is useful to locate Pleasants within an historical tradition, but there are some important differences. Schwitters' collages of refuse are aesthetically arranged and very sensually pleasing in a way that seems precious when compared to Pleasants' matter-of-fact presentation. Also, the advertising fragments found in Schwitters speak of pop culture in a way that is foreign to Pleasants' work.

The shapes of the linoleum are often evocative in a Rorschachian way, although without Pleasants' presentation of these objects it is doubtful that anyone would notice the associations. The viewer, through undirected cognition, gets glimpses of meaning, but nothing firm. The artist has referred to these glimpses of meaning as "deep flashes of intuition.” Confronting these puzzling objects, as they are presented in combination, the viewer must construct meaning as an archeologist does, taking the individual objects as clues, and interpreting the interrelationships with both the conscious and unconscious mind.

The piece "False Assumptions" consists of a folding beach chair facing towards the wall. On the wall is a piece of light blue linoleum with a decorative rolling wave pattern. Leaning against the linoleum are two mop handles, one pink and one blue, each the height of a child. One has a wire hoop that makes it appear even more figurative. In my first reading, I understood the chair as a fictive observer, and the mops as the observed figures against the implied seascape of the linoleum, possibly a parent watching two children play by the shore. My responses to the chair, which appears to be quite old, suggest feelings of time passing, memories of childhood vacations and summer idylls. The title, however, twists my confidence in this Proustian rush of associations. Is it me or Pleasants who has transformed the discarded objects into a rich implied narrative.

Another interpretation highlights the pink and blue mop handles as gender coded by color, while their forms contradict that coding: the pink is actually more phallic and the blue more vaginal, pointing toward another "False Assumption." With all these literary, narrative, and associative readings occurring, we must simultaneously keep in our minds the formal and literal realities of the materials to appreciate the artist's juggling act of the physical and metaphysical levels of this piece.

In a recent series based on Old MacDonald's farm in which the various animals from the verses of the nursery rhyme are found in the accidentally produced shapes, the idea of coincidence is forefronted. The shapes are not always immediately identifiable. The temporal aspects, the viewer's changing perceptions over time, are important to the experience and understanding of the pieces. Pleasant's work has always required an investment of time from the viewer. The animals' heads appear like abstract random shapes until one pops into clear recognition, with or possibly without having consulted the title, and then in a flash all the other heads appear. You are left wondering how you could have seen them as anything else. It could be said that the viewer completes the pieces by going through the same process of discovery that the artist went through to make the pieces.

These works, while elegant in their simplicity, are not conventionally seductive, and they require the viewer to invest time and consideration before they reveal themselves. He leaves the pieces open ended and the viewer may participate by making layered associations.

In the past few years, the attention of the art world has focused on a number of artists using found or bought items, which are altered as little as possible and are merely recontextualized to generate meaning. This tradition descends to Duchamp and Schwitters, occurring again in varied forms in Pop (Warhol’s replicas of Brillo boxes), Post-minimalism (Morris’ felt structures), Italian Arte Povera, the French Nouveau Realiste, and, in recent years, in the work of Haim Steinbach and Annette Lemieux.

Craig Pleasants’ work is unique in the current art climate. At its best, the work simultaneously functions on the multiple levels of the physical and the metaphysical, the private and the social, and comes into full flower of meaning under the gaze and involvement of the viewer.

Bill Arning, New York City, August 1989

Arning's commentary / review is detailed and descriptive. Thanks for sharing his views of your work.

Wonderful work and really nice commentary.